Got your attention with that provocative title? Good.

No, I absolutely don’t want Wikipedia to be less Free in terms of copyright and licenses and all that. I wrote the Wikipedia:The Free Encyclopedia essay on the English Wikipedia, and I still totally support it.

With that out of the way, there’s another aspect of “Free” in the Wikipedia world, which is not frequently discussed, and I’ve just realized that it’s kind of important.

What is the most translated book in the world? The Bible, of course. Why is it the most translated book? Because there are people who are emotionally attached to it, who want to spread it around the planet, and who are willing to donate money to organizations who translate and distribute it, and these organizations are actually good at what they do.

It’s not so important that it’s the Bible that happens to be the most translated book. If it wasn’t the Bible, it would be something else: some other religious book, or The Declaration of Human Rights, or The Communist Manifesto, or Romance of the Three Kingdoms, or Twelfth Night, or The Little Prince. I mean, what is the Bible? It’s a book; it has a beginning and an end. Sure, different Christian confessions can argue about the Apocrypha, the sequence of the books, the inclusion of some verses, the translation of some theologically significant words, and so on, but this is also completely unimportant for our issue; most of the Bible is the same in all confessions.

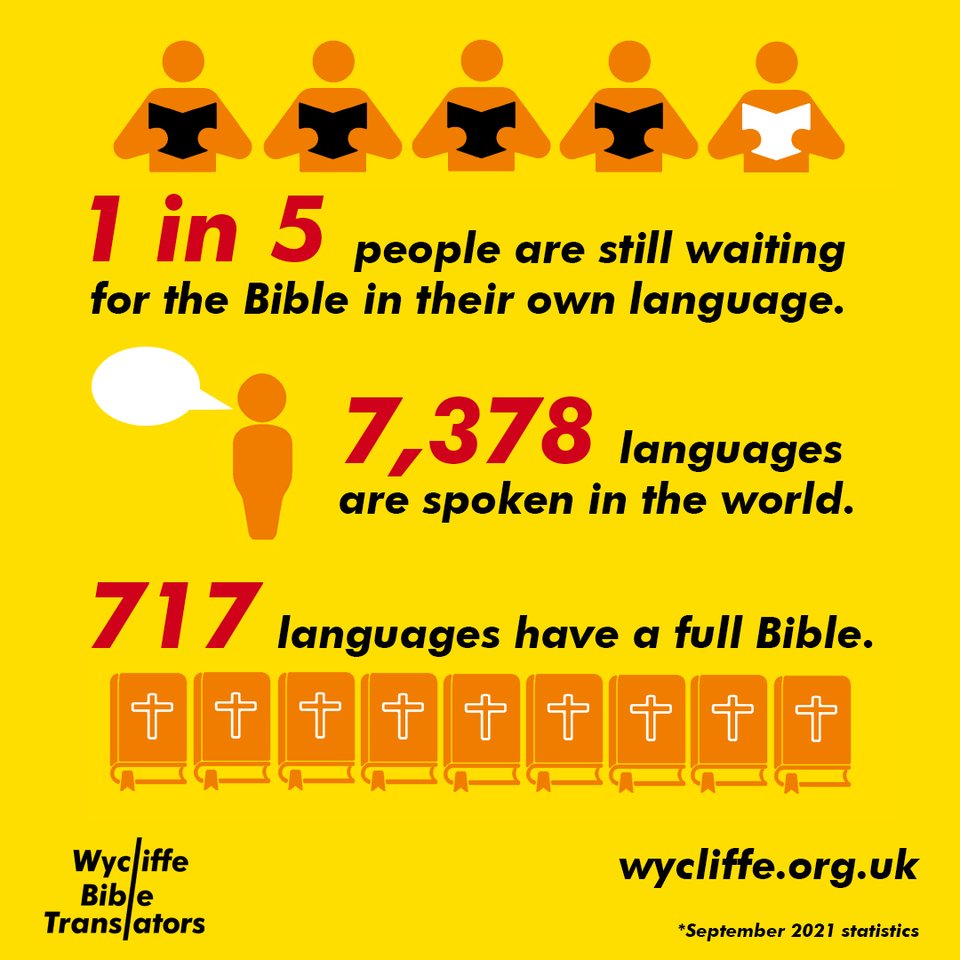

Now, because I love translation, I quite often read about organizations who engage in translating the Bible: Wycliffe, SIL, JW, Latter-Day Saints, etc. Wycliffe, for example, can publish an image like this one:

They can speak about “a full Bible” and to give a count of how many languages have one, because they know what the Bible is.

It’s not about religion. You could just as well make such a report about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or about Things Fall Apart. And you don’t even have to make such a report about these famous, iconic books: I’m sure that in the marketing department of every Hollywood studio there are people who make dozens of reports like this about translating movies every year. Like books, movies have a beginning and an end. So it’s really not about the Bible; the Bible just happens to be one book that attracts exceptional fame and emotion, so it’s useful as an example.

But could you make such a report about Wikipedia? Not quite.

That’s because we don’t really know what Wikipedia is. Unlike a book, it doesn’t have a clear beginning and an end. In languages that have an active Wikipedia editing community, it is changing so frequently, and so differently from other languages, that we can’t define what is “a Wikipedia” in a way that “translating Wikipedia” would mean “writing all the same things, just in another language”. You could perhaps say this about a single Wikipedia article, and you’d have challenges even with that, but you can’t say it about a whole Wikipedia.

We can make technical statements: “There is a Wikipedia in English; There is a Wikipedia in Japanese; There is a Wikipedia in Zulu; There is a Wikipedia in Hungarian”. For each of these languages, there is a *.wikipedia.org domain, and it leads to a website that has the same name and the same puzzle globe logo, and runs on more or less the same software platform. There is some overlap in the articles that each of these sites has, but defining this overlap is too elusive.

Having a domain does not necessarily mean that there is a full-fledged Wikipedia in a language. A Wikipedia needs articles and readers. For example: Intuitively, we can say that while the Zulu Wikipedia is not worthless, it is not nearly as useful to Zulu speakers as the Hungarian Wikipedia is to Hungarian speakers, even though both languages have a comparable number of speakers. The one in Zulu has much fewer articles and readers than the one in Hungarian.

So does it mean that to be useful, the Zulu Wikipedia has to translate all the articles from the Hungarian Wikipedia, or the English one? No. I have proof, which is also based on my intuition and not on data, but I doubt that anyone will reject it, even though it’s somewhat paradoxical. I’d argue that the Hungarian Wikipedia is more or less as useful for Hungarian speakers as the English Wikipedia, even though it has much fewer articles. Within the country of Hungary, the Hungarian Wikipedia gets more than twice the pageviews than the English Wikipedia does. This probably means that the Hungarian Wikipedia editors are quite good at guessing what things do other Hungarian speakers want to read about, and in writing articles about them, so Hungarian speakers are usually able to find lots of things they need there without having to search for it in another language (or giving up because they don’t know any other language). Unfortunately, the Zulu Wikipedia is not there yet. I know a few Zulu Wikipedians and they are wonderful, but it will take some time and effort to make the Zulu Wikipedia into an online encyclopedia that is as useful and robust as the one in Hungarian, or Hebrew, or English.

But still, even though it’s based on some data, all of that is mostly intuition. It all sounds correct, but we have no precisely defined way to measure it comprehensively. We can precisely answer the question “how many languages have the Bible” or “how many languages have Winnie-the-Pooh” because we know what these books are, but we cannot precisely and usefully answer the question “how many languages have a Wikipedia”, because we don’t know what “a Wikipedia” is.

We can know this about a certain small part of Wikipedia: the localization of its software platform, MediaWiki. The list of strings to translate is well-defined. It often changes, because the software is being actively developed, but on any given day you can easily get a report that says: “Language X has Y% of the software needed to run Wikipedia”. That’s because the software is largely the same in all the languages (with some caveats); in other words, it has a beginning and an end.

OK, but the software is not that useful without the content. So why don’t we similarly define what articles must exist in a Wikipedia to determine that it is a Wikipedia, and that it’s actually useful?

Well, because of that other subtle freedom: The community of Wikipedia writers in every language is free to decide which articles they want to write, and what is encyclopedically notable or non-notable for them. This freedom is generally a Good Thing: People who live in different countries and speak different languages have different needs and interests, and no one in their right mind should want to enforce a list of what Wikipedia articles must exist on people from another culture.

But what if we could suggest such a list? In a way, we already do: There’s the somewhat-famous List of articles every Wikipedia should have. That list has a bunch of problems, however.

It is manually curated by… some people, with whose Wikipedia usernames I’m not familiar. I have nothing against them; the work they do may be very good, but I don’t feel like they are widely recognized as an authority. I might be wrong.

In addition, how is this list used structurally? What can you do with it, other than just read it? There are some bots and Wikidata queries that measure how well does the Wikipedia in every language cover the topics on that list. For example, there’s an automatic report of which articles from this list are missing in each language. While these tools may be convenient for experienced Wikipedians, I doubt that they are good at encouraging masses of potential editors to improve the content coverage in their language. (Again, do correct me if I’m wrong.)

Finally, it is just one such list. While the articles on it may indeed be important for all of humanity, people who speak different languages will need additional articles about things that interest them. Of course, this list doesn’t try to enforce its own exclusivity, and people are free to create additional custom lists that match their cultural and regional needs… but that brings us back to the problem: Sure, freedom to make your own lists is good and essential, but if people in every language have to reinvent the wheel and do it manually, it’s difficult and inefficient. And if it’s not done systematically and uniformly for all languages, you can only use intuition and not precise measurement to decide whether a language really has a Wikipedia or not.

And that, I’d say, is too much freedom. Wikipedia should be a bit less free in this regard. I’ll repeat: No, not to force people to write about things that other people in another country decided that they must write, but to have a global way to decide on a task list, of what should be done and what was done already. A nudge.

Do I have anything to suggest as a fix to this problem? Not much, except identifying it: We cannot usefully define a Wikipedia, and we can only know it when we see it.

Still, what I can think about is a two-part approach. The first part is formulating a global community policy to determine at which point does a Wikipedia become really useful. Don’t call it “rules”; call it “recommended guidelines for measurable sustainable growth”. Sounds bureaucratic in the style of U.N. and E.U., but read it carefully—I actually mean it. If done well, it might work. By “work”, I mean “get Wikipedia in all languages to grow and become more useful for people who speak these languages”.

It would include things such as:

- A global list of articles that every language should have, with globally important topics. Notice: should, not must! The “List of articles every Wikipedia should have” can probably be a starting point, but the discussion about forming and updating it should probably be wider, more structured, and endorsed by some recognized community body, such as the Board or the Language committee.

- A local list of articles that a language should have. The list itself will be different in each language, but the method to build it will be the same, so that languages can be compared.

- The expected length of each article and some heuristic quality markers: section headings, references, links, etc.

- An expected number of how many people write these articles, proportinally to the number of people who speak the language.

- An expected number of how many people read these articles, proportinally to the number of people who speak the language (this can be measured by counting pageviews in regions where each language is spoken).

- A method to update these lists and the policy itself.

And the second part is building structured, integrated technical tools that help implement that policy:

- Entering the lists into a structured database (that is, not a free-form wiki page).

- Tracking the progress of the Wikipedia in each language from being just a domain with some test articles fresh out of the Incubator to being a full-fledged Wikipedia that people regularly edit, read, and rely on. “Tracking” means auto-generated tables, charts, and progress bars.

- Nudging people to come in and contribute to achieving that goal for their language by writing or translating articles, improving (“wikifying”) existing articles, and so on.

Why would people want to coöperate with these rules and use them? Maybe they won’t, and that’s OK. But from my years of talking to people from all over the world who want to create a Wikipedia in their language, or who want to develop the one that they have, I repeatedly heard that what they want is a Wikipedia, mostly like the one in big languages such as English, French, Indonesian, or Russian, but in their language. It’s unreasonably difficult to do it without first defining what a Wikipedia is, and doing it in a way that relies on definitions and guidelines and not only on intuition and freedom.

Thanks for this piece!